Music from the Carpathian Bow

In June of 1941 the Germans with the help of Hungarian troops launched the "Blitz-krieg" (Lightening war) on the Soviet Union. Their progress was extremely rapid. In a few days they swallowed all of the Ukraine. In a short time they were at the gates of Moscow. Right behind the advancing troops came the so called "Sonder Commando" (Death Squads), whose task was the killing of all Jews and Communists. That was the time when Hitler's genocide program was begun in earnest. That was when the notorious massacre occurred at "Babi Yar." About a month later the Hungarians, in partial compliance with German demands, arbitrarily seized a number of Jewish men, women and children and deported them to the Ukraine, handing them over to the German "Sonder Commando" to be murdered, only they called it "Resettlement." My father was one of the victims. I will never forget that scene. On that day as I arrived home from Grandfather's, I found Father gone and Mother in tears. When I enquired about the whereabouts of Father, I was told that the gendarmes took him away. An inordinate rage welled up in me. I was overcome by a sense of despair and helplessness. As I moved mechanically towards the door, to do what I didn't know, Mother barred the way, afraid of losing me too. I nevertheless got out and hastened to the gendarme station where the people were held inside a tall wooden fence. Soon they were loaded on the bus. By that time Mother and my brothers were there. The bus was surrounded by armed soldiers. Somehow Morris who was then twelve sneaked into the bus and sat on Father's lap crying. Responding to Mother's tearful pleas, a gendarme got Morris off the bus. As I was approaching the bus in a state of stupefaction, I was hit over the head with a rifle butt and ordered to leave. I was in such a state of shock that I felt no pain at all. I watched Father sitting on the bus. The look on his face was an image that has been haunting me ever since. He looked utterly alone, in a daze, bewildered. There is a sense of guilt smoldering in me for not having made an effort to join him. Somehow I feel that I have abandoned him. A large crowd was gathered outside and I noticed many of the Ruthenian women crying. After the deportation a rumor circulated that the people were lined up in front of a ditch, made to undress and gunned down. At that time I thought it a false rumor but now I know better. The murderers didn't even allow them the luxury to die with dignity. After the bus left, I went back to Grandfather to find him standing on the veranda dressed in his Sabbath garb as if ready for a religious ritual. He was grim faced, silent, pale and had an almost defiant look on his face. I wondered and still do whether his faith in a merciful God was still unshakable in the face of this horrible reality, and whether he still believed that things happen for the best as he used to say. I felt then that if there was a God, he was either a cruel one or dead. In view of the evidence of man's inhumanity to man manifest to this day, my views haven't changed much.

It was also in July, 1941, that Uncle Moishe, Dachel's husband, was arrested on some trumped up charge and taken into the counter-espionage headquarters in Mukatchevo, now called Munkatch where, to extract a confession, he was tortured. The methods of torture included cigarette burns on the skin, the pulling out of finger and toe nails and hanging by the testicles. Although innocent, when he could stand it no longer he signed a confession. When at the trial he recanted, the judge asked why he had confessed. He said he was coerced and that if he had been asked to admit that he killed his own mother, he would have had to do so. The judge, obviously a decent person, acquitted him.

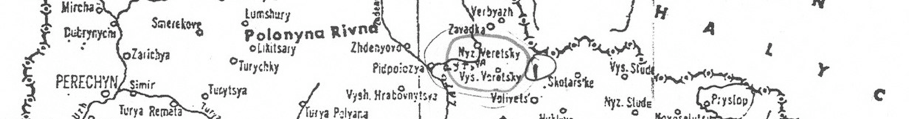

In August of 1941 a man who was smuggled over the border was deposited in the night in Grandfather's house. This was a Jewish Viennese professor who had been deported to Poland or the Ukraine. He was extremely nearsighted and his eyeglasses had been confiscated by the Germans. I don't know how he managed to escape. We promptly ensconced him in an empty cottage whose inhabitants had been deported, where he stayed while we were contemplating what to do with him. Meanwhile we carried food to him every night. As it was obvious that he couldn't stay in Verecky where everyone knew everyone, we decided to transport him to Munkatch, a large city where he wouldn't be noticed. But how was this to be accomplished? A Jewish neighbor, a grocer, owned a covered wagon with two horses which he used to travel to Munkatch once every two weeks to buy supplies for the grocery .He was asked to hide the man under the hay and transport him. He expressed a willingness to do it but only under one condition. That the man be delivered to the southern edge of Verecky where he would pick him up. As he lived in the Northern end, he was afraid to drive through the main street, which he had to do, where the gendarme headquarters were located. My female cousin, Dachel's daughter, and I volunteered for the mission. We had several choices on how to accomplish this, all fraught with peril. During the night the streets were patrolled by the gendarmes. To lead the man through the side streets in daylight was considered dangerous as only Ruthenians lived there. The option we decided on was to lead him through the main street in broad daylight. This we felt, although risky too, was least likely to attract suspicion. That is what we did. We strolled leisurely through the town holding hands, delivering him to the spot where he was loaded on the wagon and taken to Munkatch. On the way we saw several gendarmes standing on the sidewalk in front of their headquarters. Fortunately they didn't notice anything out of the ordinary. Although we risked our lives in this enterprise, for some reason I felt no fear. I looked on this as a form of resistance, defiance and revenge and I felt good about it. When the grocer returned from the trip he asked me to sell him the "mitzvah" (worthy deed). Of course I declined, saying that he didn't have enough money to buy it.

Memoirs

Boris Segelstein